We imagine spaces which slightly confound, solemnly stand up to us, hold our attention and with intention create lasting value over a multitude of generations – both in an intellectual and in an extremely direct, basic, emotional sense. We believe this can be achieved through listening, and then a conscious balancing of at-first-glance apparent contradictions and jarring harmonies, levels of incompleteness, or overlapping fragments of not-so-obvious (even questionable) coherence – finally resulting in places of endearing, novel and meaningful relationships.

Kindergarten, Vimperk, CZ, 2024–ongoing; 1,100 m²; Competition 1st Prize; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Project Architect: Dawid Roszkowski; Local Partner in Realisation Phase: prodesi (Marta Macáková, Pavel Horák, Anna Teršová), Prague; Client: Public (Mesto Vimperk)

The new kindergarten of Vimperk is anchored to its location, aligned parallel to a datum – a row of trees alongside a ditch leading down to a marshland surrounded by existing, small, artificially arranged "mountains". It then fans out in a staggered formation. All classrooms have direct access to the garden and contain open corners to bring in south-west sunlight. The body is characterised by calm, simple, timber construction. A continuous roofed-over deck space allows for the possibility of communal interaction during recess – this extended plane, covered with plants and photovoltaic panels, also provides for passive natural protection and regulation of solar radiation. The building appears as a compact unity from the exterior, but upon entering, children discover a space like that of a village – made up of shifted, individual house-like blocks. The corridor is wide enough to be used for playing in rainy weather, as a gallery, or as an extension of the multipurpose room for larger community events. Skylights provide openings with various orientation to the sun, thereby throughout the day subtly yet physically rendering evident its movement in relation to the earth... They also resemble horns (?), or the previous garden sheds tossed up, scattered over the roof (?), or ... (?)

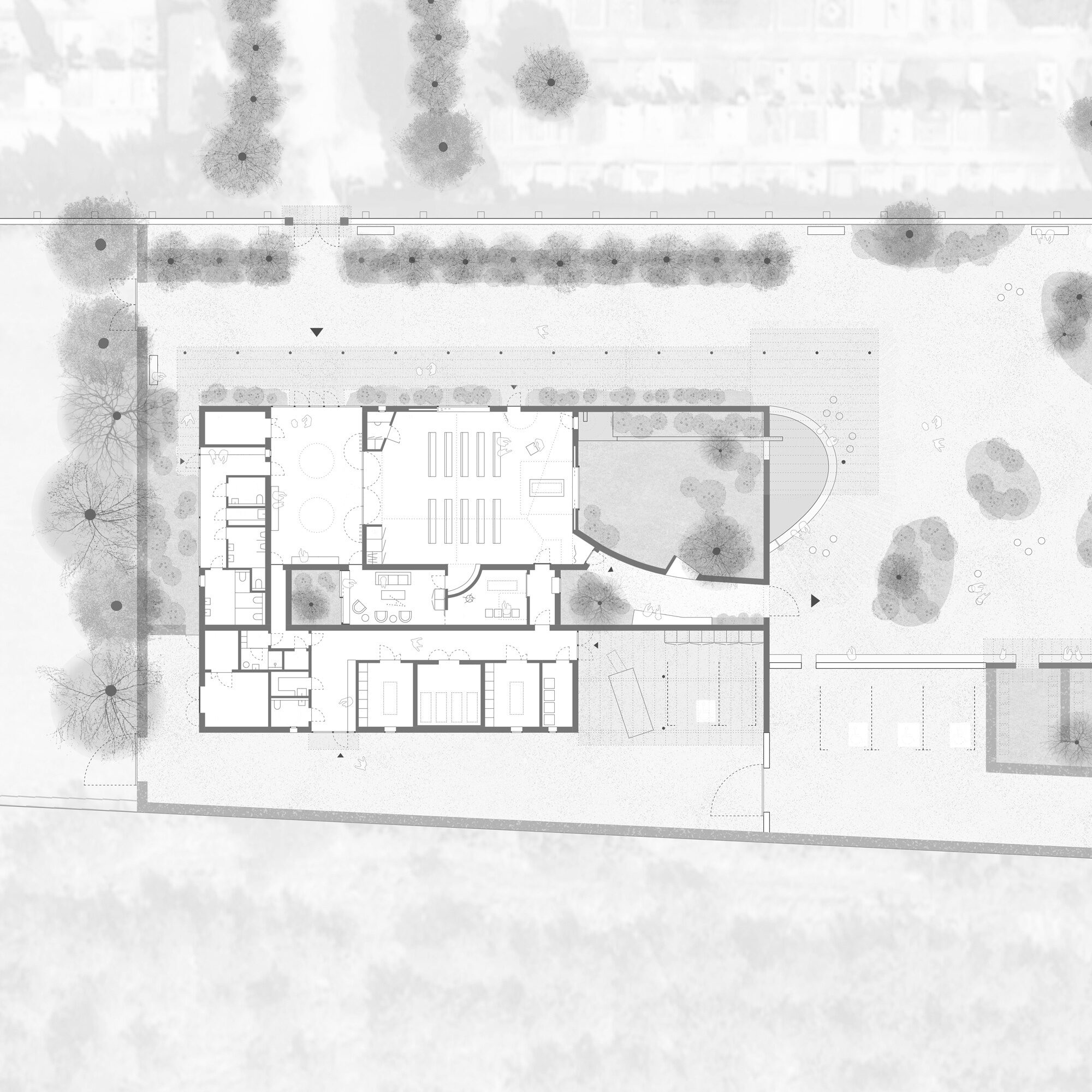

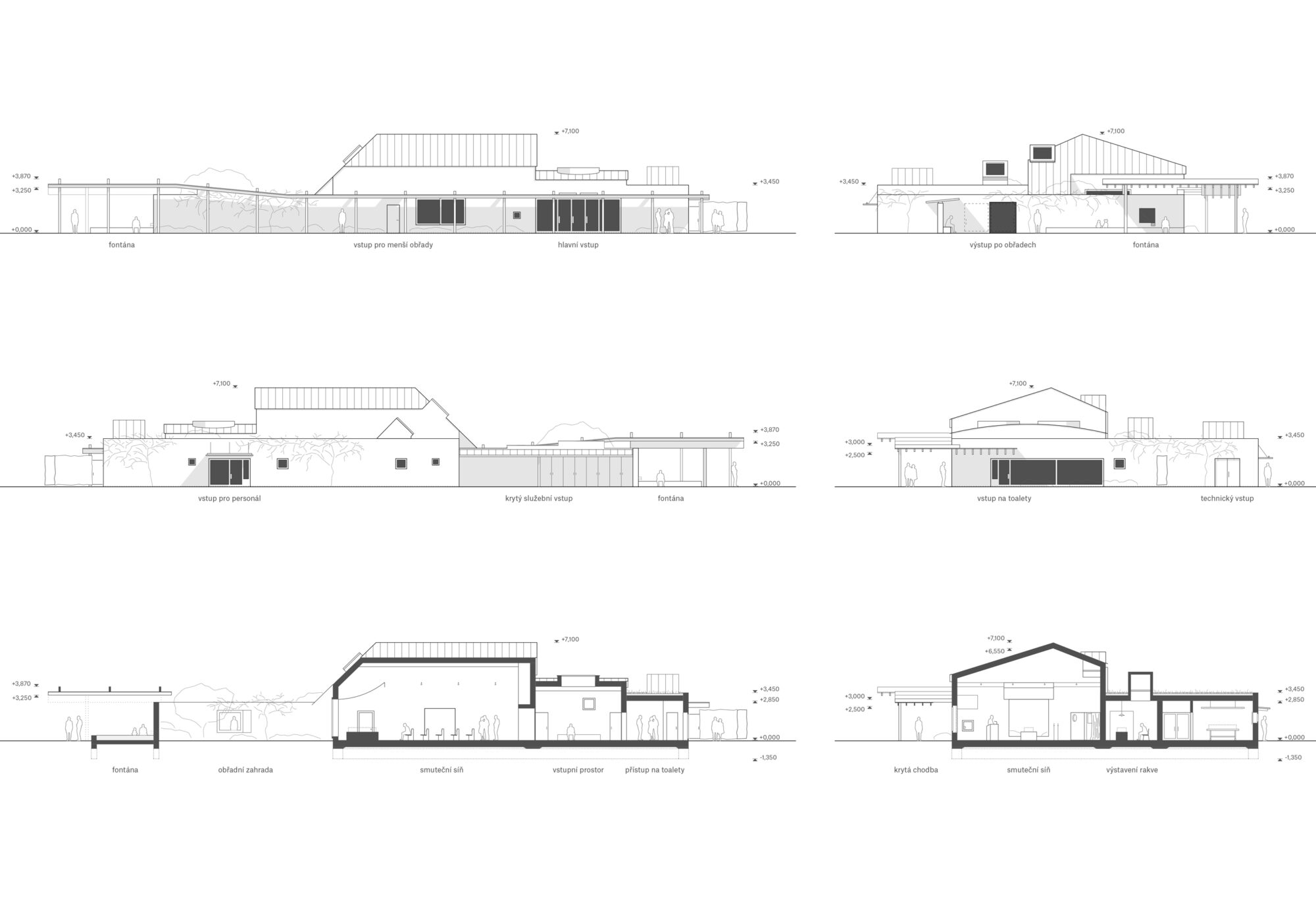

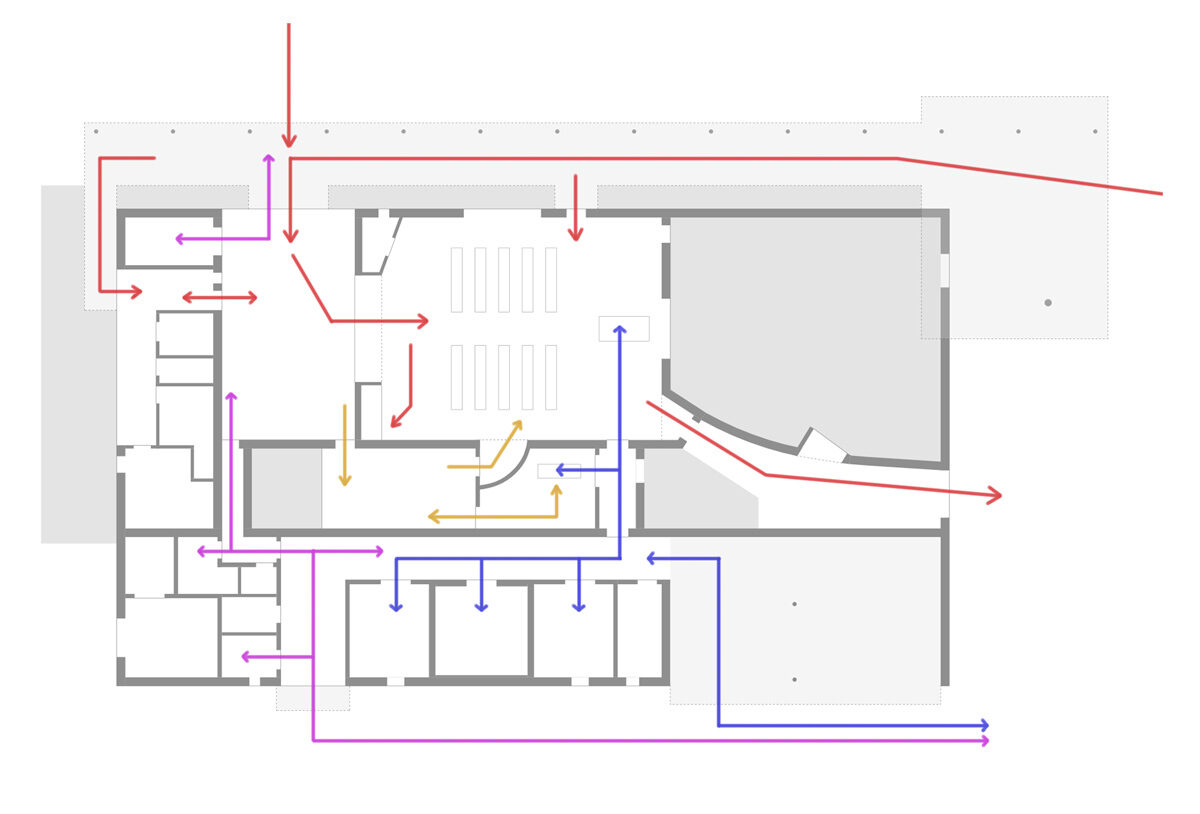

Cemetery and Funeral Hall, Podebrady, Nymburk, CZ, 2025; Building: 560 m², Landscape: 12,140 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Images (exterior): mukko studio, Warsaw; Client: Public (Municipality of Podebrady)

A ceremonial hall connects to the existing north-south axis of the old cemetery as well as a new pathway running from east to west. A forecourt contains small flower meadows, providing dignified spaces for the scattering of ashes. In the garden, benches invite quiet reflection and contemplation. An airy roof rises upwards, gracefully welcoming all who enter from the east. Visitors can gather here before proceeding inside, sitting on the edge of a fountain that emerges from the garden wall. They then continue together along the covered path toward the entrance. After the ceremony, mourners may pass by the body of the deceased and exit through a narrow courtyard with trees leaning over the walls, although never accessing the garden seen behind the casket. Finally, they return once again to the forecourt with the fountain and flowers. The newly planned cemetery area to the east offers a range of burial options: traditional graves with coffins, columbaria, urn burials in ground plots, and the possibility of scattering ashes beneath a memorial forest.

House, Cuglieri, Sardinia, IT, 2025; 125 m²; Project; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Assistance: Arch. Filippo Garau (Cagliari); Client: Private

A narrow, tower-like house is adjusted to expand space and generosity of light on the upper floors with the removal of a slab in one room and a new stair. An irregular, textile ceiling drops and figuratively dances down to mitigate the two varying roof heights.

Garden Walls, Pianspessa, Ticino, CH, 2022–ongoing; 800 m²; Direct Commission; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Atelier Carrera, Minusio; Collaborator(s): Melina Almpani, Dario Biscaro, Florian Elbing; Structure: Ingegneri Pedrazzini Guidotti (Roberto Guidotti), Lugano; Construction: Pietro Calderari, Stabio; Client: Private (Fondazione Pianspessa)

A walled production garden towards the summit of Monte Generoso also acts as a visual plinth for an impressive country house – neither a purely aristocratic type nor a rough construction lacking an overriding order. The building is a reconfiguration attributed to the architect Simone Cantoni (1739–1818), in which an old farmhouse was mirrored, thereby incorporating it into a plan resembling a palace type. Our project for the garden and its dry-laid stone walls takes the site’s palimpsestic history into account in its logic and detailing of construction. The work serves as a precursor to ongoing planning for transformations of the existing and additional buildings by Atelier Amont, Atelier Carrera, and giulia & hermes killer.

Two Pedestrian and Cycle Bridges, Diepoldsau, St. Gallen, CH, 2024–2025; 7,100 m²; Competition 5th Prize; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Structure: Bergmeister (Patrick Studer), Bülach; Landscape: OePlan (Kenneth Dietsche), Altstätten; Images: Barbara Gołebiewska, Warsaw; Client: Public (Gemeinden Diepoldsau/Widnau)

The main bridge was designed in anticipation of a planned renaturalisation of the riverbed for future flood protection. While the current site reflects the canalised Rhine, the bridge already orients itself to the profile of the future floodplain. No extension will be necessary, as was originally proposed in the competition brief. All elements — superstructure, piers, abutments and access routes — are based on the future dam geometry, but remain fully accessible in the current situation. Only minor adjustments will be required to modify the infrastructure once the landscape is altered. Two columns support spans of 85 / 108 / 85 meters. The parapets function as beams. Towards the eastern side, the deck drops down as a ramp to reach the current terrain. After the landscape work, this section will be simply raised up to create a continuous platform arriving at the future dam’s height. For the first twenty years a stair provides passage back up to the last stretch, granting access to a look-out platform into the forest – suited to bird and/or raccoon watching. A secondary bridge traverses the Alter Rhein.

Two Multifamily Houses, Rothenburg, Luzern, CH, 2024–2025; 4,780 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Landscape: Jan Minne, Brussels; Client: Private (Röm.-kath. Kirchgemeinde Rothenburg)

Twins - two large houses - surrounded by trees, bordering a field, and a small pocket of dense forest. Balconies reach around towards the sun. Nonetheless, we aimed for a simple house – to repeat – once. Jan, the gardener, designed diverse worlds within worlds. Jonas humanised things, smudging and shaking.

Transformation of a Rowhouse, Bachletten, Basel, CH, 2024–ongoing; 140 m²; Direct Commission; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Structure: Schmidt & Partner (Gernot Hörtnagl), Basel; Construction Management: Stefan Apitz, Basel; Client: Private

Interior partitions and slabs are removed to expand space, allowing ample sunlight to reach the depth of the plan. Windows on the upper floor are pushed out onto the parapet to capture the old balcony, creating a long working area with an integrated desk spanning wall to wall. Independent elements are loosely attached to the facade: a filigreed, generous entrance roof with thin posts for plants to climb up, a large dormer, awnings of various types, and a terrace with loose steps and a planter cascading down to the garden.

Mountain Refuge, Engelberg, CH, 2024; 65 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Florian Elbing; Structure: Bergmeister (Patrick Studer), Bülach; Construction Management: Martini Schäfer (Ralf Schäfer), Basel; Client: Private (SAC Sektion Engelberg)

The proposal addresses both the existing tectonic conditions of the site and prevailing regulatory and territorial parameters. Accordingly, the new shelter is sited in close proximity to its predecessor, aligned with the inter-cantonal boundary. Situated marginally below the summit, it refrains from asserting dominance over the landscape while offering a vantage point toward the western glaciers. The entrance to the cabin is arranged to minimise the risk of being buried in a snowdrift.

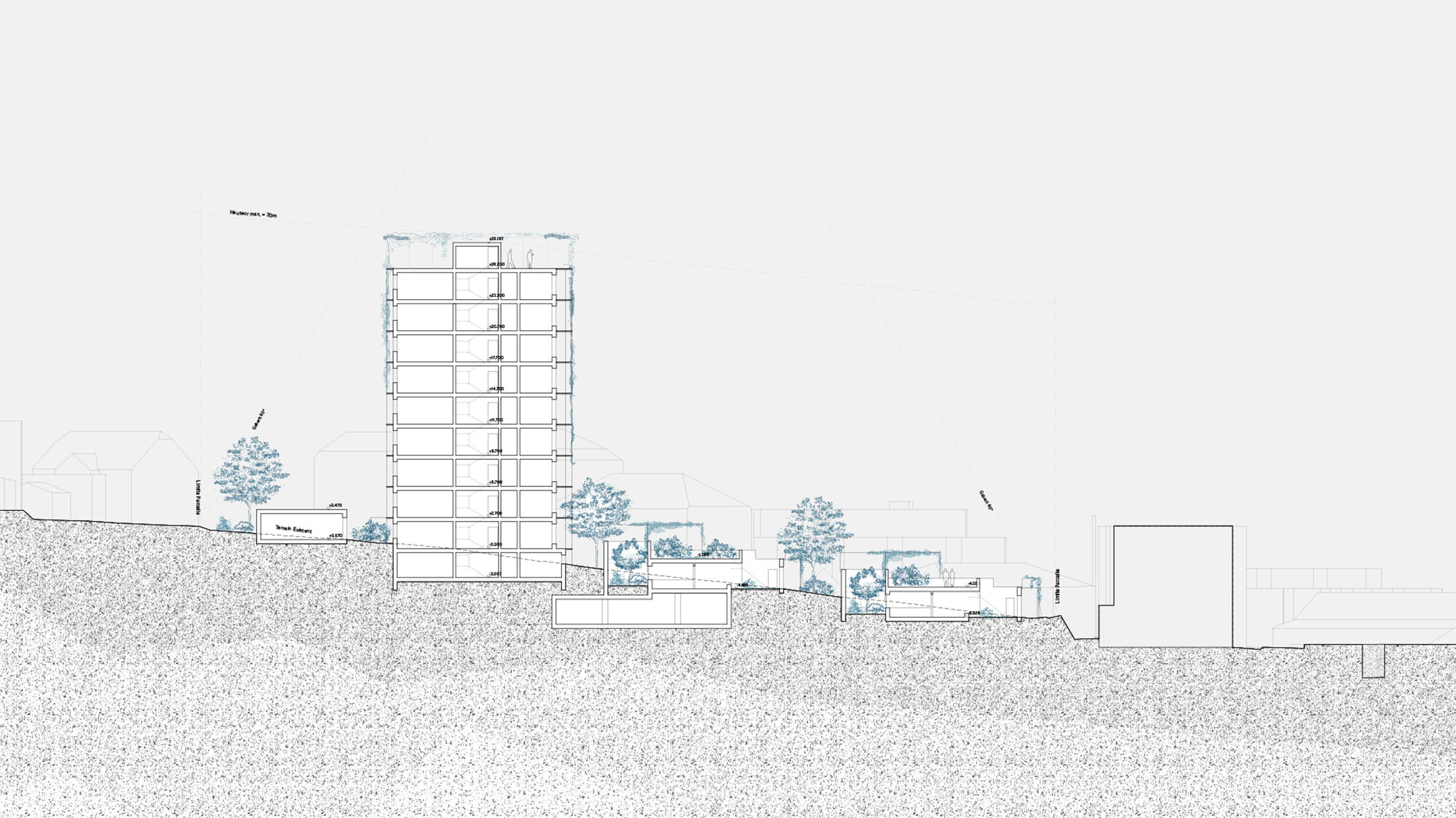

Dwellings for Elderly Residents, Valasske Mezirici, Zlín, CZ, 2024; 2,900 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Florian Elbing; Client: Private

Private, exterior areas of each apartment retain the qualities of both balconies and loggias – they extend from the building for a distant view, but also retreat into it – therefore residents have the feeling they can choose if they are exposed or prefer to be more protected, based on where they sit. All apartments have two means of access to this outdoor room, providing the possibility of circulating in a loop throughout the dwelling.

Priority is given to a generous common room on the ground floor, resulting in a clear, singular place to socialise with others. A resident would make a conscious choice to go there and consequently behaviourally adapt oneself (perhaps in spirit and in appearance) to that intent. This attitude in spatial planning is critical of the current general tendency – in elderly housing – to enlarge hallways into an endless expanse of shared living rooms, wherein there is a total lack of hierarchy. A hangover due to the experience of seriality need not result in the license to employ lazy haphazardness...

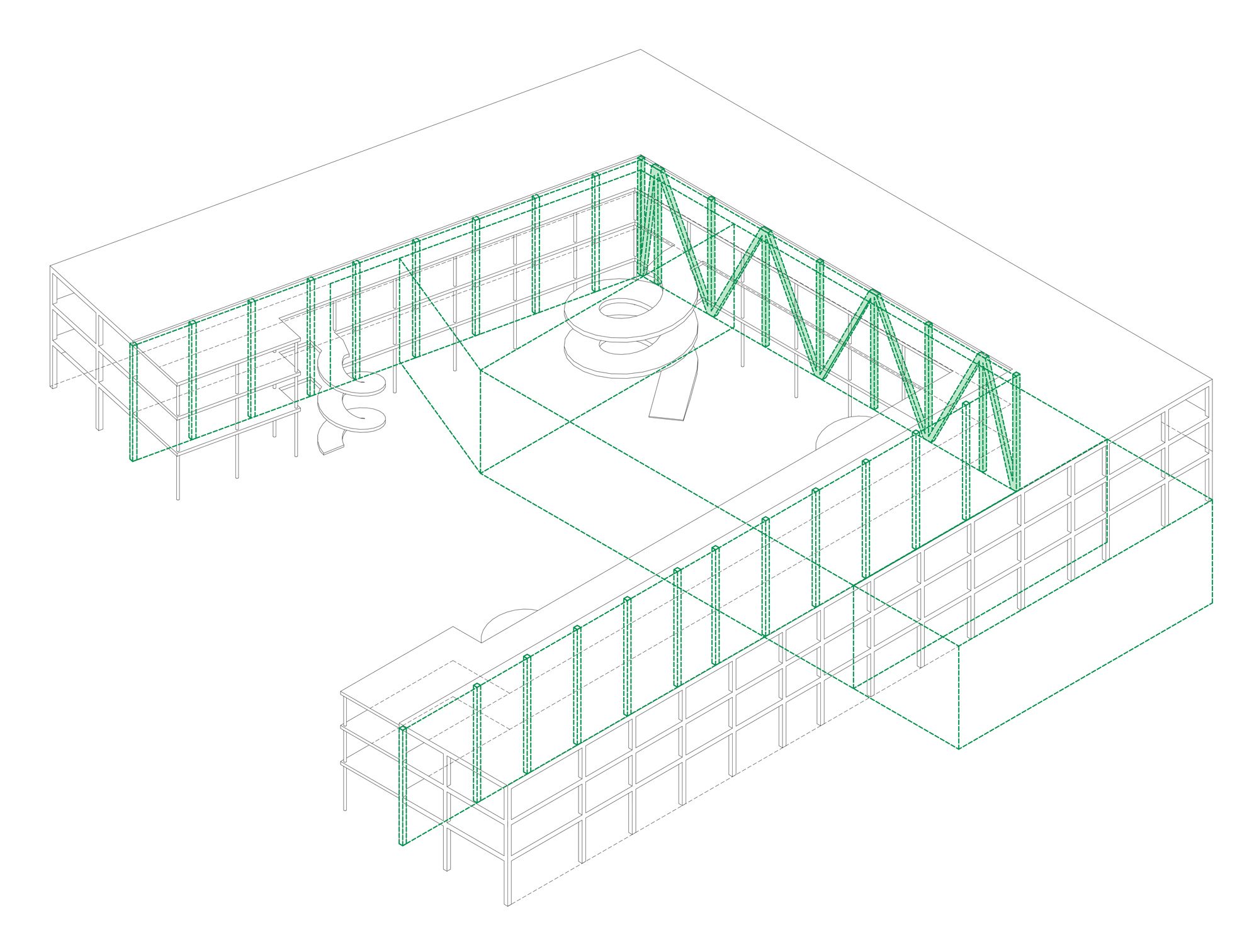

Community Centre, Riehen, CH, 2024; 3,800 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Florian Elbing; Landscape: Dominika Wasik, Basel; Structure: wh-p Ingenieure (Lars Keim), Basel; Client: Public (Freizeitzentrum Landauer)

The community centre presents itself as a spacious, public garden house, nestled behind tall, broad-leafed, shade-granting trees. A light-structured pergola overgrown with climbing plants harmoniously connects all three buildings – new and old – to form a clear ensemble. The main building is placed directly on top of the existing underground floor (intelligent foundations on unstable terrain) and re-uses its wooden elements in a generous re-configuration.

Garden Restaurant with Observation Tower, Malešický Park, Prague, CZ, 2024–ongoing; 380 m²; Competition 1st Prize; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel & Architect Jonas Løland, Oslo; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Haomiao Zhai, Florian Elbing; Structure: Finn-Erik Nilsen, Oslo; Client: Public (Praha 10)

Visible from afar as a hybrid, jewel-like machine and a clear landmark, the restaurant and tower should serve as a symbol of pride and identity for the surrounding Malešice district. The inclined, tripodal construction invites different solutions and experiences along its height – providing places to perceive fauna and flora and their changes throughout the seasons. Like the multitude of views from the tower, its asymmetrical appearance is diverse – some might see in it floating petals, rising decks of an ocean liner or machine parts. As a casual meeting point, it will improve the quality of stay for the park – contributing to its atmosphere by offering spaces for leisure and relaxation within the restaurant at ground level, or active recreation in the tower above, all within a single life-affirming entity.

City Hall, Romanshorn, Thurgau, CH, 2024; 5,530 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Dominika Wasik; Structure: Monotti Ingegneri (Mario Monotti), Locarno; Biodiversity/Ecology: Kevin Vega, Zürich; Reuse: Zirkular (Andreas Oefner), Basel; Client: Public (Municipality of Romanshorn)

A banal supporting structure is clearly ordered and designed as a hybrid, economical system of steel columns and beams, spanned by HOLORIB composite floor decks. This ensures longevity of use over several generations, while the internal partitions of timber can be reorganised as per necessary. Moderate spans between columns dictate material savings for beam and slab thicknesses while ensuring flexibility in the layout of offices. Beams set loads onto continuous columns, which transfer directly to foundations. As an exceptional instance – for communal benefit – the atrium skylight and the roof to its side are supported by long, transversal beams – resulting in a porous transition between the central circulation space and the exterior terrace.

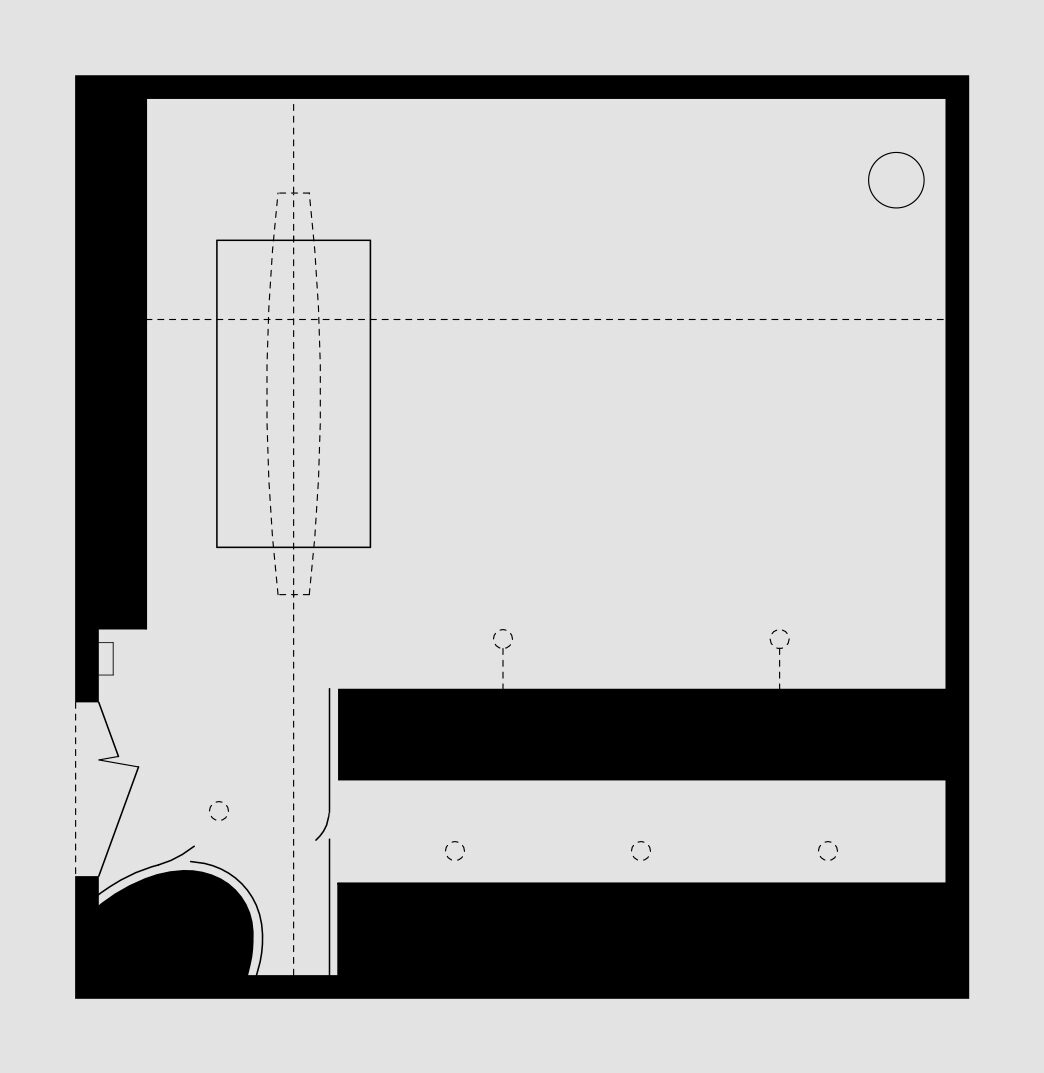

Nová Alšova Jihočeská Museum, České Budejovice, CZ, 2024; 8,600 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Haomiao Zhai, Dawid Roszkowski, Florian Elbing, Dominika Wasik; Structure: IngAtelier Studer (Patrick Studer), Zürich; Client: Private

Floors are staggered, such that visitors are always aware of proceeding spaces, maintaining a view of the path to reach them through a central atrium. One is subtly aware of the entire space, without ever actually seeing it directly at once. Various distances between slabs (clear heights of 3.9 to 5.3 meters) allow curators to take advantage of diverse spatial proportions. Continuous, ribbed skylights on the roof lead one upwards, creating variety in light characteristics, and offer a natural ending to the promenade.

Cabin, Awajishima, Hyogo, JP, 2024; 60 m²; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Florian Elbing; Client: Private

Tightening and densifying practical, everyday necessities leaves space for emptiness up above. Something resembling a particularly heavy rucksack allows other areas of the facade to be freed up, for the benefit of the inhabitants – tense, in order to relieve.

Pedestrian and Cycle Bridge, Bellevue, Geneva, CH, 2023–2024; 12,000 m²; Competition 6th Prize; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Haomiao Zhai, Florian Elbing; Structure: IngAtelier Studer (Patrick Studer), Zürich & Simon Karrer, Zürich; Images: Barbara Gołebiewska, Warsaw; Client: Public (Commune de Bellevue)

A light, steel bridge glides calmly (gracefully/contrastingly) above a hectic motorway (typical for the place), passing down parallel along the shore of Lake Geneva. Midway, a staircase provides a short-cut, descending perpendicular towards the water's edge. As a mediator/base, a massive ramp – of earth and concrete – rises to catch (or to release?) the metal structure. Here, a cut-out hole in the solid parapet allows for animals (such as dogs, raccoons, muskrats, opossums, et al.) or small children to pass directly out to the fields or the adjacent playground.

Primary School & Kindergarten, Zuoz, CH, 2023–24; 1,830 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dominika Wasik, Dawid Roszkowski, Florian Elbing, Haomiao Zhai; Structure: IngAtelier Studer (Patrick Studer), Zürich; Client: Public (Municipality of Zuoz)

Primary school and kindergarten classrooms are grouped in separate areas and arranged across four floors with a minimal footprint, to leave as much of the land – on the rather cramped site – free for the garden ... these are mountain children after all. Within a residential area of the village, the building expresses itself ambiguously, blurred between that of an institution and/or simply a large house. A light, playful, floating terrace significantly increases the amount of exterior area available.

Transformation of a Cemetery, Horw, Lucerne, CH, 2023–24; 18,200 m²; Selective Competition 2nd Prize; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel & Balissat Kaçani, Baden; Collaborator(s): Joel Brandner, Sibel Besir, Dawid Roszkowski, Florian Elbing; Structure: IngAtelier Studer (Patrick Studer), Zürich; Biodiversity/Ecology: Franz Paul Horn & Michael Gräf, Vienna; Lighting: fokusform (David Weisser), Zürich; Images: mukko studio, Warsaw; Client: Public (Municipality of Horw)

Unser Vorschlag für die Umgestaltung des Friedhofs Horw folgt nicht dem Konzept, dass Friedhöfe einfach nur Parks sein sollten wie jede andere urbane Landschaft auch. Wir haben uns darauf konzentriert, die Grenzen des Friedhofs aufzuweichen und eine Vernetzung mit der Nachbarschaft zu schaffen, indem wir klare Schwellenräume definieren. Mit der Umgestaltung wollen wir aber den traditionellen Charakter eines Friedhofs als ruhigen und kontemplativen Ort der Anbetung stärken. Neben der bestehenden christlichen Prägung bieten wir ein breites Spektrum an säkularen Bestattungsformen mit landschaftlicher Wirkung.

Church & Community Centre, Trondheim, NO, 2023; 1,600 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Melina Almpani; Structure: Dr. Minu Lee, Zürich; Client: Private (Charlottenlund Kirke)

The structure over the main hall consists of deep, glued laminated timber members that traverse the short span as simply supported beams. Loads from the roof are distributed laterally over a solid timber slab. The lower curvature allows for a slight contribution from arch action to aid in the load transfer, of which the horizontal thrust is absorbed by the circumferential walls. Due to the relative slenderness of the cross-sectional profiles, supporting beams are placed laterally between the main girders to prevent the compression chord from buckling.

Community Hall, Rzeszów, PL, 2023; 3,300 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Dominika Wasik, Sibel Besir; in cooperation with 2pm architekci, Warsaw (Piotr Musiałowski); Client: Public (City of Rzeszów)

Upon entering, visitors encounter a generous common atrium – the heart of the building. From here, all public rooms and the roof terrace are accessible from a stair which adjusts its configuration at each floor, encouraging openness and exploration. Each level contains a distinct function, thereby a respectively unique flight of steps identifies it. The central cavity can be considered much like a dynamic, mediaeval city square – where a variety of people have the chance to casually encounter each other.

Lakeside Promenade, Parks, Public Squares, Gardens, Gallery Spaces, Ateliers, Restaurant, Kiosk, Pavilions, Cabins, Orchard & Bridge, Lugano, Ticino, CH, 2023; 67,000 m²; Selective Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Taiko Amont, Dawid Roszkowski, Dominika Wasik, Edoardo Reverberi, Melina Almpani, Ella Jonuzi, Sibel Besir; Structure: IngAtelier Studer (Patrick Studer), Zürich; Landscape Consultant: Gohl Landschaftsarchitektur GmbH, Basel; Heritage Consultant: Arch. Roi Carrera, Minusio; Energy/Sustainability/Lighting: Luca Gattoni, Origlio; Biology/Botany: David Johannes Frey, Melano; Museographic Concept: Loredana Müller, Camorino; Flotation Technics: Bluet Floating Solutions, Vantaa (Finland)

Multifamily House and Office, Bassersdorf, Zürich, CH, 2023; 1,060 m²; Competition 2nd Prize; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Landscape: DUO Landschaftsarchitekten (Sandra Kieschnik, Magda Pawlowska), Lausanne/Bern; Client: Private (Reformierte Kirchgemeinde Breite)

Although comparatively large within the context, our intention was for this building (comprising an office, semi-underground parking garage and six apartments of various sizes) to be read as a single house within a forest. Through exaggerated exceptions in articulations such as balconies, vertical pergolas, and a chimney, any clear repetitive order is subverted. As the orientation and form of these elements all vary, inhabitants can easily identify their own dwelling from out in the garden or along the street.

Office Building, Warsaw, PL, 2023; 3,100 m²; Study; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Project Architect: Dawid Roszkowski; Client: Private

A clear order of columns and window frames allows flexibility – calibrated for both small, individual rooms and an open office arrangement. A continuous, circumferential bench acts as a beam, reducing the number of supports, and thereby the interferences in plan, to a minimum. All non-load-bearing elements are modular and allow various configurations. On the ground floor, a café and a spacious foyer provide a porous and inviting entrance. The top floor consists of an open-air terrace and the upper half of a large, double-height conference room.

Flora/Fauna Reserve and Park, Guardavalle Marina, Calabria, IT, 2023; 134,000 m²; Competition 4th Prize; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; in cooperation with Atelier Hembra, Reggio Calabria (Arch. Silvia Giandoriggio, Ing. Francesca Maria Pavone, Ing. Domenico Giandoriggio, Geol. Alfonso Aliperta); Client: Public (Municipality of Guardavalle Marina)

Fire Pavilion, Yangshuo, Guilin, CN, 2023–2024; 70 m²; Direct Commission; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Melina Almpani, Dawid Roszkowski; Structure: Dr. Neven Kostic, Zürich; Client: Private (Yangshuo Sugar-House Hotel)

A hanging pavilion is to be built to commemorate the coming new year. It is based on the idea of separation between raised, other-worldy flames, and a lower, useful fire. For warmth, people may gather around the lower pit for the months before the main event. In the end, the upper bundle of long bamboo poles will be set ablaze, as part of a continuous, contemporary ritual.

Public Square, Restaurant and Kiosk, Palmi, Calabria, IT, 2023; 6,400 m²; Competition 5th Prize; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; in cooperation with Atelier Hembra, Reggio Calabria (Arch. Silvia Giandoriggio, Ing. Francesca Maria Pavone, Ing. Domenico Giandoriggio, Geol. Alfonso Aliperta); Client: Public (Municipality of Palmi)

A public square next to the town hall of Palmi is arranged on a central axis, with a Roman column standing in line with the entrance. Our proposal retains these elements, yet besides these commonplace characteristics, takes note of a slope from one corner to its diagonal opposite. Since this is apparently fixed within the collective consciousness (locals refer to it as piazza scivola), we added a long, linear fountain, which accompanies the fall of the slope and places the column also in its respective centre. The irritation is thereby pointed out (a poke in the eye), integrated, and the tension is celebrated rather than left as an unfortunate, unresolved coincidence – CHARISMA! Pavilions – at the edges – define the head/tail of the fountain, and reinforce a loose and distorted symmetry, while leaving the central space open for various events.

House, Oristano, Sardinia, IT, 2023; 85 m²; Project; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Dominika Wasik; Assistance: Arch. Filippo Garau (Cagliari); Client: Private

Porous rooms – rather than connected to each other directly – are arranged along the edges of a walled garden.

Primary School, Gelterkinden, CH, 2023; 2,130 m²; Competition 1st Prize; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Ella Jonuzi, Melina Almpani; Landscape: studio erde. (Violeta Burckhardt, Marcel Troeger), Zürich/Berlin; Structure: wh-p Ingenieure (Lars Keim), Basel; Sustainability: Dario Biscaro, London; Client: Public (Municipality of Gelterkinden)

Considering the town’s future expansion plans, our proposal leaves a yet-to-be-finished area above the entrance, open to the landscape and available for multifarious uses.

Transformation of an Apartment, Warsaw, PL, 2023–2024; 65 m²; Direct Commission; Architecture: Atelier Amont; Project Architect: Dawid Roszkowski; Client: Private

Various, and in some cases operable, openings between partitions create a perceived depth greater than actual dimensions. Colors and subtle alterations in the scale of objects – such as lamps – or the thickness of shelves, further exaggerate this effect (while at the same time having sense for other, atmospheric or structural, rationale). A fuzzy light-body greets one at the entry and participates as a loose focus amongst rooms – analogous to a hearth.

Collective Housing, Fields C/D, Walkeweg, Basel, CH, 2022; 17,400 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Giulia Guizzo, Dawid Roszkowski; Landscape: ESTAR (Aurora Armental Ruiz, Stefano Ciurlo Walker), Geneva; Structure: wh-p Ingenieure AG (Giuseppe Morlino), Basel

The proposal offers an aggregation of homes suited to a wide array of potential customs of living (a significant proportion were reserved for refugees, to provide, as the program stated: 'places of retreat' which we wholeheartedly agreed with as a direction) – from contained courtyard types to more socially interactive gallery access flats – arranged in such a way as to be mutually beneficial and to form a meaningful and consolidated neighbourhood. As with other recent competitions in Basel, the city provided a database of materials available to re-use. Within an insulated layer, these were integrated in a straight-forward manner to maximise their structural efficacy.

House & Studio, Littu di Zoccaru, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2022–2023; 80 m²; Project; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Client: Private

Only sleeping rooms, built into the hillside, and a study above, are insulated and closable with doors and windows. The remainder of the areas are left open to the elements (and haphazard visitors), under a large, shade-granting roof.

Housing and Kindergarten, Schliengerweg, Basel, CH, 2022; 1,900 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Structure: Wojciech Kapela, Warsaw; Client: Public (City of Basel)

The city of Basel set a goal for this competition of utilising, to the greatest degree possible, re-appropriated elements salvaged from nearby demolition sites. Most of these materials in our proposal are painted or stained in a homogenous colour – thereby creating an order while leaving subtle traces of the actual mess (we enjoy this both/and-ness). Desiring not to focus exclusively on these issues (we still intended it to be a house for dignified human beings; adults and children – and not only a didactic exercise in novelty), we also attempted an urbanistically sincere proposal – the building completes a narrow, linear block, but refrains from closing it. Instead, it expresses a distinguished face to the south, and steps back from the ground floor, granting an independent character for the entrance to the kindergarten. The western garden then remains visually, and physically available to various communal uses. Upper floors are expressed as parts of a single, large roof, rendering the overall size ambiguous – assisting in situating it within an area of heterogeneous volumes.

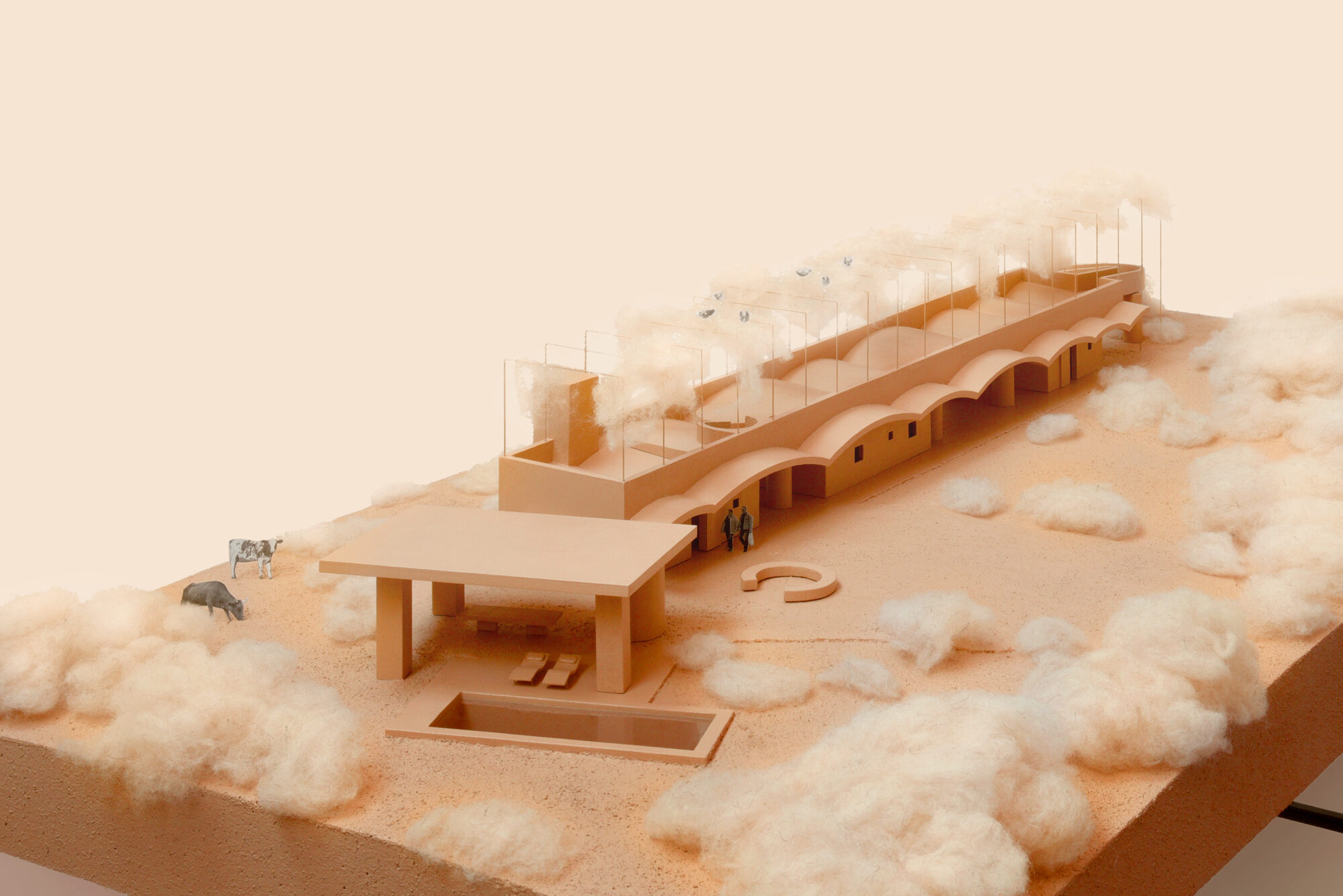

Cabins & Hotel, Bastianazzu, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2022; 1,850 m²; Study; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Client: Private

Approximately fifty cabins are arranged, in a dispersed configuration – as in a primitive camp – utilising light-weight, mostly timber components and only punctual foundations: accommodation for travellers without a substantial impact on the flora and fauna of the existing landscape.

Farmers' House, Lu Sulianu, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2022; 130 m²; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Nikki Sedigh; Client: Private

A new house is planned on the same natural-stone foundations as a ruined stable (of which the granite and ceramic tiles are re-used for new retaining walls and paving). The upper layer of the roof is completely covered by a pergola entwined with lush Vitis. This provides a generous, otherworldly space for contemplation and strolling (similar as at the philosopher's path in Kyoto) in the mornings and evenings; while the shade generated by dense leaves passively cools the house throughout the day. The grapes, once harvested from the vines, offer both sustenance and pleasure for the bovine and human inhabitants of the farm.

Restaurant, Li Puzzi, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2022; 140 m²; Study; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Dominika Wasik; Client: Private

Opaque roofs and shading screens float, without an obvious order, offering protection and informal places for sitting, dining and merriment. The density, arrangement and differing heights of roof planes produces a variety of space and gradients of intimacy (A Pattern Language), to suit the mood and/or personality of each guest. (i.e. are you looking for a party, or would you prefer to be off to the side in the shadows ...?)

Transformation of a Row House with Three Floors, Isola Rossa, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2022; 180 m²; Study; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski, Nikki Sedigh; Client: Private

The lift, bathroom, emergency stair, and wardrobe are all situated as

if they were pieces of loose furniture, varying in height, nonchalantly

shoved aside within an empty, narrow plan. One space thereby "meanders"

between the objects, admitting ample light from both the north and

south facades. Although without the intention of being so, its resultant

character is similar to that of a canyon – which however, once

realised, after deliberation, influenced further adjustments. Rather

than a typical gable roof, which would subtly halve the space of the top

floor – here the semi cylindrical cross-section reinforces the notion

of a single room.

Gerresheim Cemetery, Düsseldorf, DE, 2022; 29,000 m²; Workshop Lead: Logan Amont; Participants: Sibel Besir, Darcy Carroll, Shauneen Cavanagh, Christoph Grüter, Chen He, Matthew Lindsay, Francesca Masserdotti, Edoardo Reverberi, Giovanni Rinaldi, Dawid Roszkowski, Nikki Sedigh, Wilusty Tengara, Zhouyi Tu, & Meng Wang; Guests: Emilie Appercé, Matthew Bailey, Marianne Meister, Ioannis Piertzovanis, Joseph Redpath, Anna Staudt, Heinrich Toews, & Liviu Vasiu

Over a period of eight days in February 2022, we met for a workshop to discuss and reconsider basic aspects of cemeteries for the present. Participants were assigned fragments to concentrate on – in some cases in relation to other colleagues’ proposals – and to develop their ideas through models. On the suggestion of Anna Staudt, a stonemason who is engaged in national seminars on the topic, we used, loosely, the Gerresheim Cemetery in Düsseldorf as a basis for our speculations.

Download a PDF documentation of the final works of the participants.

Theatre, Lucerne, CH, 2021–22; 15,500 m², Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Piertzovanis Toews, Basel; Collaborator(s): Thibaut Dancoisne, Lukasz Palczynski, Norman Price

A porous, long foyer – an invitation to the city – offers a dynamic experience, much like a fragmented stage-set. Various balconies, stairs and bridges potentially trigger the spatial sensation of spectators being at the centre of communal life. The typically defined roles of actors and audience thereby become blurred.

Urban Housing, Baufeld 5, Voltanord, Basel, CH, 2021; 14,500 m², Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel & Marco Salina, Geneva; Collaborator(s): Chen He

A series of slender, parallel volumes are linked together at lower levels by hedges and high, floating screens of pleached trees, leading to an ambiguity in urbanistic reading. The complex thereby forms a block, yet is also a repetition of singular bars – leading to improved sunlight and ventilation for all flats. As opposed to built mass, plant-life stands in to fulfil the spatial definition society requests, but is subversive to a degree, remaining porous at ground level.

Alterations to a Historic Public Garden, Klosterinsel, Rheinau, Zürich Canton, CH, 2021; 10,800 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Chen He

Looking at Klosterinsel Rheinau, we took into account the current assets – and avoiding demolition as much as possible, attempted to improve and render appropriate those elements which seemed out of accord with the surroundings and history of the place, often by adding additional, mediating layers. It is therefore not a reductive approach and is not a return to any pure origins, but rather carefully evaluates all artefacts for their inherent energy and contemporary relevance

[..]Pavilion of Reused Materials, Dreispitz, Basel, CH, 2021; 95 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborators: Chen He, Bingwen Wu; Team (on "stand-by"): Akane Moriyama, Stockholm (Textile), RSL Rebediani Scaccabarozzi Landscapes, Milan (Garden)

A world, consisting of re-used or re-appropriated elements, is assembled to provide diverse, dynamic opportunities of use and experience. Reclaimed bricks, being of substantial weight, are set on the ground with a temporarily binding mortar, creating an artificial landscape – a plinth comprising generous planters, and a continuous surrounding bench. Windows are lifted up onto scaffolding or steel profiles, to act as roofs, defining space and protecting certain areas from rain and providing shade from the sun, aided by thin strips of dyed textile. Everything is painted or rendered

[..]Artist Residences/Hotel, Orani, Sardinia, IT, 2021; 280 m², Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Luigi Fabozzi, Paolo Failla; Client: Private (Costantino Nivola Museum)

A series of slabs, cast into the cliff face, slope down, granting shade and shedding off rain. The mountain and the roofs provide shelter guests need for a short time.

Urban Park & Nature Preserve, Quartier Volta Nord, Basel, CH, 2021; 22,200 m²; Competition; Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Chiara Filippini

Along a thin plot, public "rooms" of various character of fauna and flora, humid/dry, are linked one after another with a threshold strip of a hilly nature preserve allocated adjacent to the railway lines. The project, emphatically, avoids romanticising historical attributes such as the lines of rails which until recently covered part of the site, but rather orients itself towards resolving the problems presented, while positing a place of joy for the future.

Courtyard for Cultural Events, Schaffhausen, CH, 2021; 9,350 m², Competition; Landscape + Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Luigi Fabozzi, Paolo Failla; Structure: wh-p Ingenieure AG (Lars Keim), Basel; Traffic Planning: moveIng AG, Basel

The design for the Kammgarnhof creates a socially dynamic, multi-layered and ecologically rich complex for the surrounding urban environment of Schaffhausen. It is a place offering a range of activities for all age groups, but the boundaries of such are not clear – effectively overlapped to encourage an exchange between individuals. Its goal is to offer a festive, playful atmosphere, complementing and reinforcing the qualities of other public spaces of Schaffhausen such as the grandiose Herrenacker Platz, the contemplative Kloster Allerheiligen, or the park-like character of the Mosergarten.

Anno Museum Extension, Hamar, Hedmarken, NO, 2021; 2,600 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Atelier Guo, Shanghai; Collaborator(s): Chen He, Zhiwei Liu

Our proposal for an expansion to a museum, containing a restaurant and additional gallery spaces, is a compact, linear building (essentially the only option due to the strict confines of the program and boundary lines). It is a typical 'Janus-face', with disparate character along its respective, two long facades. The eastern edge towards the Storhamar barn is resolute and calm, seemingly massive behind a dematerialised wooden screen, while the opposite, facing the Mjøsa lake is vibrant and dynamic, seeking out independence, in its own unique attitude, turning away from the historic ensemble. The building is seemingly self-aware about the sensitive context it is situated within, but at the same time also regarding the intricacies of contemporary life.

Urban Park, Quartucciu, Cagliari, Sardinia, IT, 2021; 32,400 m²; Competition; Architecture + Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel, Stefano Dell‘Oro & Pierre Minio Paluello

The project consists of redefining and reconnecting various urban voids adjacent to the passage of a stream, creating a park with its own strength and identity. Nature becomes the founding and central event in the project to create a unique quality commonly perceived from all sides. A single architectural element, a pergola, unites and accompanies visitors on their journey, linking them in an ongoing dialogue with the land and its flora. One and the same element determines many aspects: pedestrian and cycle paths, bridges, playgrounds, sports & exercise areas.

Housing Quarter, Salzweg, Zürich, CH, 2020; 21,500 m², Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Gaëtan Iannone, Zürich; Collaborator(s): Marc Sanchez Alfonso; Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel

At the edge of the city, along the street, a large area is left unbuilt as an offer – a public park. The meandering, stepped-back bar clearly marks the border between the urban fabric and the agricultural fields before a forest, and is so articulated as to offer generous spatial qualities to both residents and to all inhabitants within the surrounding city. The garden-park is composed of medium to large trees with high, floating crowns, and casually terraced platforms to provide flat areas for a variety of uses.

Community Hall, Münchwilen, Thurgau, CH, 2020; 1,250 m², Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Gaëtan Iannone, Zürich; Collaborator(s): Marc Sanchez Alfonso; Traffic Planning: CSD Engineers, Lausanne; Landscape: De Molfetta Strode, Lugano

With the simple gesture of extending a roof and sunshades a substantial distance past the facade of the multi-purpose hall, a meaningful space is generated which allows for interaction with the park and sports fields. An existing barn, recommended by the program to be destroyed, is re-used for storage and warm-weather activities, and forms a gate with another new building containing after-school and communal facilities. Both are linked with a trellis of plants which becomes a pergola over the path towards the nearby river. Taken individually the three buildings appear banal, but through the serial repetition of columns at their facades (actually tension members in the case of the large hall building), the ensemble recalls a classic forum – a generous offer for the public.

Secondary School, Isengrind, Zürich-Affoltern, CH, 2020; 3,100 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Gaëtan Iannone, Zürich; Collaborator(s): Marc Sanchez Alfonso, Ayca Kapicioglu; Landscape: De Molfetta Strode, Lugano; Structure: Lorenz Kocher, Chur

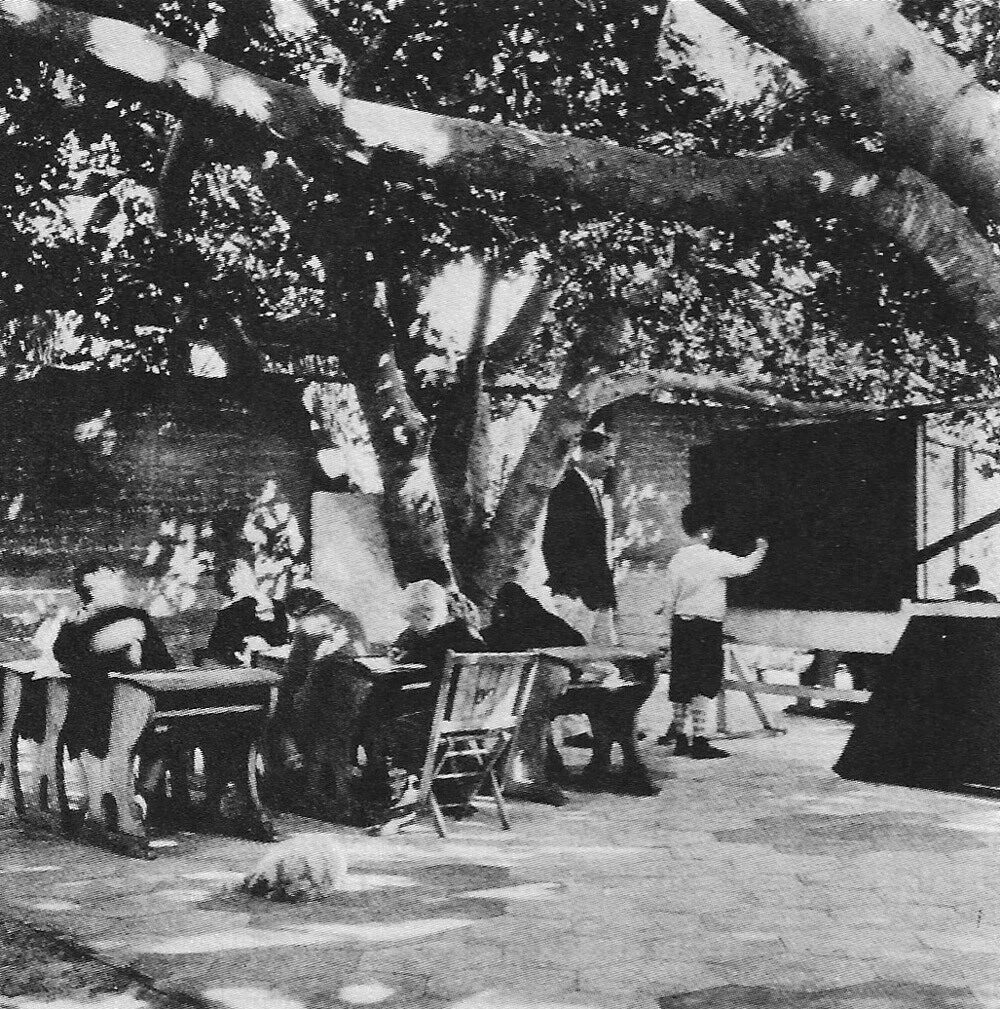

A garden is the heart of the institution, acting first as an exterior entrance hall and then as the backdrop as students move around it from room to room on a raised, covered walkway throughout the day. The filigrane wooden structure stands out from and complements the neighboring massive residential complexes, becoming a special "house for learning" in the midst of a lush garden. This can be read as a reinterpretation of the typological contrast a school building has had throughout history: in previous times, for example, in some areas of Switzerland a traditional school house might have been constructed of stone, on the top of a ridge or hill, while surrounded by lower wooden residential buildings.

House, La Scalitta, Trinità d'Agultu e Vignola, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2020–2021; 120 m²; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Client: Private

This house has two courtyards. One is contained and first experienced upon entry through a gate at the street – various rooms look onto it, and it thereby offers a microcosm for, say, a rare tree to grow so we can concentrate on it through the window, and provides a respite from and counterpoint to the immense pressure of the omnipresent draw to gaze at the Mediterranean. The other courtyard is bound only on three sides by walls, and then opens out over a pool down the hill towards the open sea. These two, somewhat opposing instances occur as events within a loose formal bonding of elements – there is no prescribed path. Any issue then in questioning of meanings is vague and open-ended – I like to think of blurring the notion

[..]Campus, Bernex, Geneva, CH, 2020; 42,600 m², Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Gaëtan Iannone, Zürich; Collaborator(s): Marc Sanchez Alfonso; Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Structure: Mitsuhiro Kanada, ARUP, Tokyo; Traffic Planning: CSD Engineers, Lausanne; Client: Public (Municipality of Bernex)

Bernex, a village at the outer-edge of Geneva, requested a campus on a site bound by a highway access ramp which excluded the possibility of building near it, thereby limiting the usable area, and as well created significant noise pollution. On the other side of the ramp an urban agricultural park is currently being planned. We proposed to turn the disadvantage into a quality by placing a continuous cap over the ramp, and then constructing, out of timber, the main classroom building overhead. Columns and minimal cores on the ground floor allow porosity – connecting the campus with the adjacent, agricultural fields. The campus in turn becomes a generous park in itself, with small pavilions containing facilities shared with the public – a sports halls, cafeteria, library and performing arts hall. A vision; a huge intervention – seemingly brutal, yet due to its existence, offers to society a serene, collective space.

Cabin, Am Trippelsberg, Itter, Düsseldorf, DE, 2020–2022; 10 m²; Project; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Dawid Roszkowski; Client: Private

A stonemason has a parcel of land at the Rhine on the outskirts of Düsseldorf where she stores extra stones, near her workshop; and plans on building a cabin to spend her midday break or weekends together with family. The cabin is thought to provide rich spatial depth, despite its relatively small size. Due to the means of openings, when one is seated on the back bench, the panels in front block the view of the sky, so concentration is focused exclusively on the flow of the river and the opposite bank – a nature preserve. This notion of filtering and contracting the conception of space is inspired by a similar framing device, at Koho-an (Kyoto) designed by Kobori Enshu in 1612.

Textile Museum Extension, St. Gallen, CH, 2020; 4,250 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel, Gaëtan Iannone, Zürich & David Moser, Zürich; Consultants: Damian Fopp & Annina Meier, Curators, Museum Für Gestaltung, Zürich

The revered museum building by Gustav Gull is 'clothed' in a new, noble costume with the addition of an attic. The entire building is understood as a unity – the existing building and the extension are rendered in a monochrome blue. The loggia of the roof allows a view from the street up into the interior, similar to the lapel of a suit. A public loggia high above the street, with a view over the roofs of St. Gallen. The roof covers the glazed front, in the form of a colonnade, like a cloth. Under this roof is both the museum café and space for workshops or lectures. Several entrances lead from the blue loggia into a large exhibition hall. A simple box, the hall extends over the entire length of the building and its size complements a range of exhibition spaces. The height of the room and the fact that it is accessible via several entrances allow it to be used in a variety of ways.

Small Apartments & Ateliers (Transformation of an Office Building), Kleinhüningen, Basel, CH, 2020; 4,150 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Gaëtan Iannone, Zürich; Collaborator(s): Zhiwei Liu

The existing structure with its serial character of columns and slabs has been preserved. Behind it is the huge Hafenbacken 1, mainly built of bricks and concrete, but with steel elements for technical aspects such as the gallery access. Our building, which has a unique character because it belongs to the industrial area, will now be part of the residential quarter on the other side of the river. It is, so to speak, part of both worlds and our proposal aims to reflect this dynamic.

House, Bessùde, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2019–2020; 90 m²; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Client: Private

A single family home is planned to be built directly at the street front, as the building regulations call for, in this historic village thirty kilometres from the western coast of Sardinia. Rather than a simple offset from the street, the proposal fills the entire plot and is generally oriented inwards to three “rooms” which are open to the sky. Space is confused and thereby expanded through a myriad of dynamic views from room to room, which have varying degrees of sunlight.

Movable Pavilion, Hamburg, DE, 2019–20 (Shown at various locations throughout Germany); 8 m²; Built; Installation; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel

An homage to the dark entrance spaces of Japanese farmhouses, blackened from the smoke of cooking, (almost) dissolving into complete shadow, yet with a small amount of light seeping in from ventilation openings ... A seemingly endless overlay of filigrane, timber elements ... Creating qualities of light similar to that of looking out of the mouth of a cave, but here, strangely, from within a small, moveable pavilion ... A moveable cave ...

Housing Quarter, Beauregard, Neuchâtel, CH, 2019–2020; 27,700 m²; Competition; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel & Gaëtan Iannone, Zürich; Collaborator(s): Constança Girbal Eiras, Zhiwei Liu, Pierre Minio Paluello; Landscape: De Molfetta & Strode, Lugano; Timber Construction Consultants: Renggli Holzbau, Fribourg

"Pendant que je marche de mon bureau en direction de Beauregard, je profite de la douce lumière du soleil se reflétant sur le lac de Neuchâtel, encadré par les alpes. Par temps clair, on y voit même le Mont Vully et on devine la Jungfrau. En cette fin de journée d’été, qui fut étouffante, une fine brise venant des forêts du Nord apporte un peu de fraîcheur. Des vieux murs de soutènements continuent à libérer la chaleur accumulée durant le jour. Tantôt ces épaulements, guidant ma promenade, s’élèvent en dessus de moi, tantôt ils se transforment en garde-corps sur lesquels on peut

[..]Study, Workshop & Archive, Am Kesselhaus, Weil am Rhein, DE, 2019–2020; 55 m²; Built; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Client: Private

Shelves built of the most common fir slats – holding documents, books and models facing onto a main, top-lit space, and otherwise tools and materials towards a secondary, darker storage area – reconfigure and partition a room in a former textile factory. Curtains screen off disorder (the "put-away" idea) to allow concentration. Hanging from the building's structural tension-rod, a long, curved, aluminium lamp casts light down during evening hours, onto a broad, working table. The 0.6 millimetre thick sheet metal was hammered, essentially folding it back and forth in minute dimensions – to prevent it from warping over a span of three metres. As an unexpected side-effect, the texture generates multifarious and fascinating reflections.

Courtyard Garden, Hotel, Todos Santos, La Paz, Baja California Sur, MX, 2019; 12,650 m²; Invited Competition; Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel

How shall we go about thinking of a courtyard garden today, especially within an arguably already beautiful landscape? We could simply let nature take-over, and then selectively trim or not. However, I believe in that case we would be missing the point. With the construction of walls for living all around, a room, open to the sky, comes into being. This presents us the opportunity of

[..]Winery and Dwelling (Transformation of a Farmhouse), Brusata di Novazzano, Ticino, CH, 2019–2021; 700 m²; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Collaborator(s): Stefano Dell‘Oro; Client: Private (Direct Commission); Structure: Enrico Pellegrini, Stabio (TI)

A farmhouse in the historically protected centre of Brusata, near Novazzano, has been transformed and extended multiple times over the past two centuries. The layers of these changes are visible and the strategy has been to retain them as such, while only making repairs where necessary and adding on yet another layer for contemporary requirements. In recent years, the current owner has started to maintain vineyards in the surrounding fields and intends to transform the building into a winery with a small apartment

[..]Garden, Riehen, Basel, CH, 2018; 2,200 m²; Study; Landscape: Atelier Amont, Basel; Client: Private

A transformation of a garden around an existing villa from the 1930s. The proposal contains two disparate realms, but developed with regard to each other, forming a meaningful unity. An upper portion is light-filled and enjoyed from a pavilion at the top of a slope, where the clients spend time dining with family or guests while looking down on shrubs pruned in cloud-like formations rising as the topography descends. The lower portion is at the bottom of the same slope, under the respective shrubs which gradually become higher at the back of the plot – creating a hidden, dark, shady world for walking alone or seeking introspection seated next to a quiet pool of water. One unique garden, like a body, offers the potential to satisfy desires for both convivial enjoyment and solitude.

House, Monti Russu, Rena Majore, Sassari, Sardinia, IT, 2017; 110 m²; Study; Architecture: Atelier Amont, Basel; Client: Private

This house is on a narrow peninsula jutting out into the sea on the northern coast of Sardinia. It therefore has two faces, that to each side of the water. A column is nearly in the center of each of these faces, marking out a point for domesticity within the wild, rocky landscape around. Two wooden rooms hang from a concrete structure, one for sleeping, the other for work, where the client prefers to concentrate, in privacy. They are like caves, but are light and suspended. A pool on the roof is accessed from stairs within a central core, which also contains the bathroom and a place for cooking on an open fire.

Summer Pavilion, Hasselt, Limburg, BE, 2013–2014; 85 m²; Competition 1st Prize, Built; Architecture: Atelier Amont; Collaborator(s): Liaohui Guo (Project Architect), James Jamison, Taiko Amont; Textile: Kvadrat; Furniture: Elmar Heimbach, Aachen; Structure: Robrecht Keersmaekers, Brussels; Client: z33 House for Contemporary Art

A competition called for a place of meetings and events to be a focal point for an art festival situated between the two cities of Hasselt and Genk. The temporary pavilion was placed alongside the Albert Canal, thereby signifying it as a fleeting element, akin to a boat ashore for a brief period. It was designed to be both welcoming and to open out to the surrounding landscape as well as to create an intimate atmosphere using curtains of thick cotton tarpaulin, adapting to the specific requirements of various events. The building is composed of

[..]Fountain in a Garden, Former Setouchi Governor’s Residence, Setouchi, JP, 2010–11; 35 m²; Built; Landscape: Atelier Amont & Yoshinobu Aiba; Client: Private (Direct Commission)

A fountain in Naoshima is constructed of river stones from Kyoto, where we were based and could be transported in a single load – chosen for their shape, size, and surface; and as well, in turn – the specificity of their curves influence the overall character of the intervention. The reaction to water is always present, as the stones are both above and under water – fish also sometimes splash drops onto higher dry areas. Water is held both below and above ground. Finishing mortar is dyed with calligraphy ink to create a homogeneous body.

Community Centre, Tamil Nadu, IN, 2003; 80 m²; Built; Architecture: Atelier Amont; Collaborator(s): Taiko Amont, James Jamison; Structure: Poppo Pingel, Pondicherry; Client: Private (Appirampattu Village)

Arriving in the vibrant world of south-east India, after a few weeks, bored working only at a desk, I quit my first internship. Desiring to build somehow, I raised money for materials, and with the help of an NGO, found a nearby village which wished to have a community centre. The residents contributed labor – some were trained masons – hence rammed earth foundations and compacted earth blocks were chosen to suit their experience. While struggling with the design (was it enough?), in a local newspaper (I have no idea why?) I read a speech by Luis Barragán (whose work I did not yet know at that time) – there were no images of his work, just the text ... and it was an epiphany.

FHNW INSTITUT ARCHITEKTUR – MITTAGSVORTRAG N°1

ATELIER AMONT DREAMS / RATIONALITY

Logan Amont, Basel

Mittwoch 13.03.2024, 10:30–11:30 Uhr

Raum 02.N.21

Institut Architektur FHNW

Campus Muttenz, Hofackerstrasse 30

www.iarch.ch

Critiche finali SA23, BSc2 Atelier Mayol, Arch. Jaume Mayol

Casa d'estate, Maiorca, Spagna

Lunedì 18 dicembre 2023 ore 14:00-19:00

Martedì 19 dicembre 2023 ore 9:00-17:00

Palazzo Canavée, spazio atelier, piano 2

Via Giuseppe Buffi 5, 6850 Mendrisio

Critici invitati: Logan Amont, Xavier Ros Majó

8 December 2022, Many thanks for the time in Oslo, to see the remarkable work by students of LCLA office, Gro Bonesmo & Silvia Diaconu at AHO, and as well for the generous evening following.

10 November, 19:00, Rogaland Kunstsenter, Nytorget 17, Stavanger, Norway

FORELESNING MED ATELIER AMONT. 10.11 kommer det sveitsiske arkitektkontoret, Atelier Amont til Stavanger og Rogaland Kunstsenter for å presentere sitt arbeid. Atelier Amont holder til i Basel og gjør prosjekter som omhandler alt fra mindre paviljonger til større boligbygg. Vi gleder oss til å høre mer om spennende innfallsvinkler og måter å jobbe på. Foredraget starter kl.19:00. For de som måtte ønske å møtes før, åpner kaféen en time i forkant av arrangementet. Det blir enkel servering av mat og drikke på arrangementet. Håper mange tar turen!

Thanks to Jakob, Per, Torgeir and all at @stavanger_arkitektforening for the warm welcome and wonderful mood in your city!

27 July 2022, Invited by Prof. Uta Graff, TUM Munich, to discuss Masters students' projects at their final reviews, and to give a presentation of work afterwards ... Thanks to all for the experience as well as the apéro on the rooftop! @architecture.tum

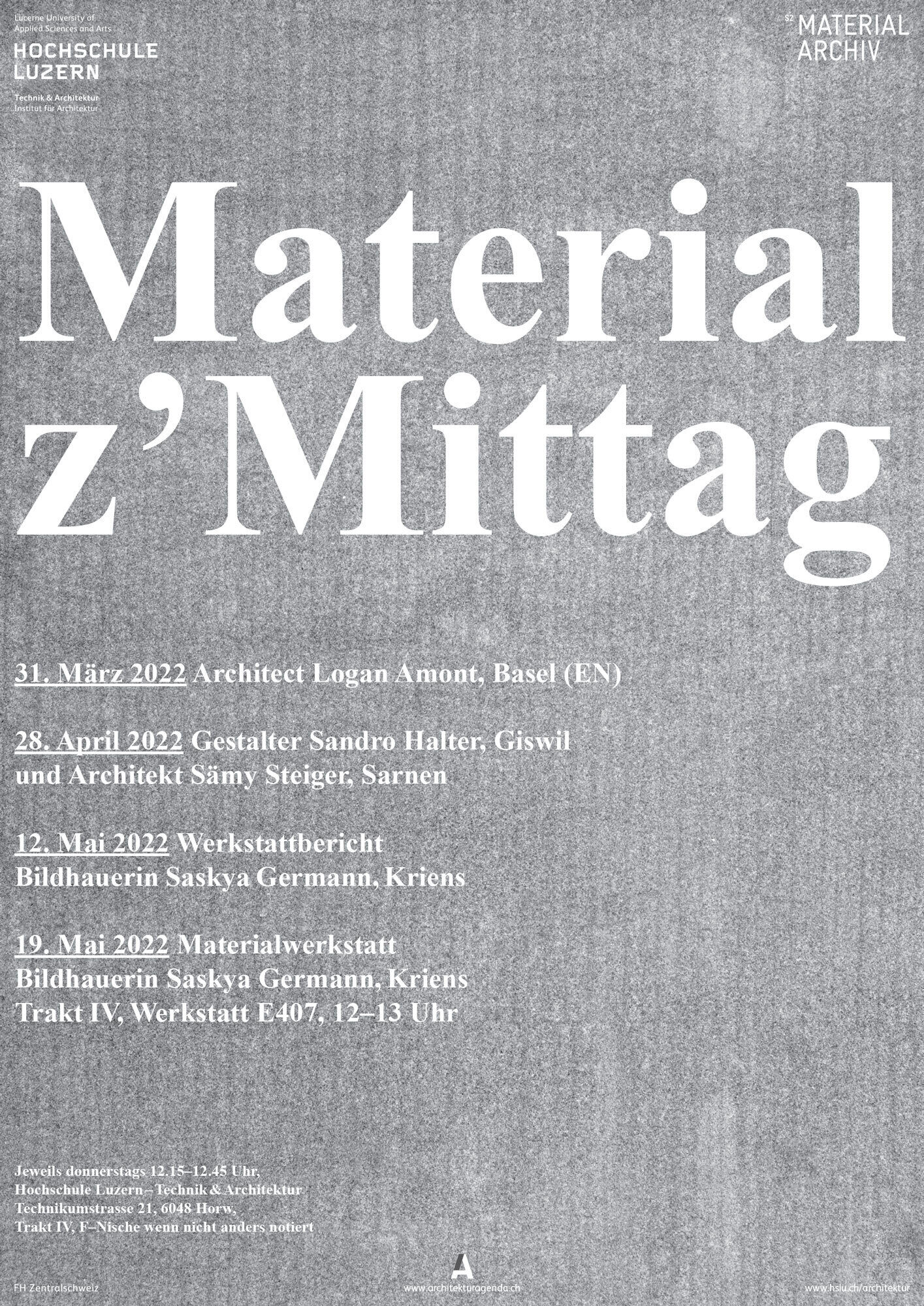

'Two Projects Using Stone'

Lecture 31.03.2022, 12:15, S2 HSLU Technik & Architektur, Technikumstrasse 21, 6048 Horw Building IV, Niche F-Level

...

1) A fountain in Naoshima is built of river stones from Kyoto – chosen for their shape, size, and surface qualities; and as well, in turn – the specificity of their curves influence the overall character of the intervention. (Fountain in a Garden, Former Setouchi Governor’s Residence, Naoshima, Japan, 2010–11; in collaboration with Yoshinobu Aiba, Gardener)

2) A walled garden for production towards the summit of Monte Generoso visually forms a plinth for an impressive country house – neither a purely aristocratic type nor a peasant’s home without an overriding order. Our project, for the garden and respective massive walls, takes this history into account, regarding its detailed mode of construction. (Walled Garden, Former Country Residence of Arch. Simone Cantoni, Pianspessa, Ticino, Switzerland, ca. 2022–23; in collaboration with Roi Carrera, Architect & Roberto Guidotti, Engineer)

Invited to a seminar to present and discuss the contemporary focus and concerns of young European practices. Organized by Vector Architects (introduction) & Team Shichai (moderation). Participants included: 刘东洋 Dongyang Liu, 李兴钢 Xinggang Li, 董功 Gong Dong, 柳亦春 Yichun Liu, 张斌 Bin Zhang, 丁垚 Yao Ding, 冯江 Feng Jiang, 郭廖辉 Liaohui Guo, & others

Invited to share work and thoughts about landscapes and public space with students at Summer School Ticino (HSLU & i2a), which took place within the impressive 'Fabbrica del Cioccolato', Dangio. Afterwards we discussed their project for the redesign of a small square consisting of a fountain and new paving in a neighboring village. Thanks to Ludovica Molo Könz, Roi Carrera & Daniel Fuchs for the experience.

Invited by Prof. Alexander Fthenakis, TUM Munich, to discuss students' projects at their final reviews, after having shared a presentation with them earlier in the semester; TUM inhabitable structures studio, @inhabitablestructures

Die Vortragsreihe »N E U B A U T E N« der Fakultät für Architektur an der TU München bringt Studenten und Architekturinteressierten zehn junge aufstrebende Architekturbüros aus unterschiedlichsten Teilen Europas näher und setzt sich mit ihren Ideen und Arbeiten auseinander.

In February, we will gather to think about cemeteries; abstractly, and practically – in relation to the contemporary situation in Germany. With guests Emilie Appercé, Matthew Bailey, Marianne Meister, Ioannis Piertzovanis, Joseph Redpath, Anna Staudt, Heinrich Toews, & Liviu Vasiu.

For interest, please read the brief.

...

Many thanks to all the participants, from China, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Poland, Romania, Switzerland & UK: Sibel Besir, Darcy Carroll, Shauneen Cavanagh, Christoph Grüter, Chen He, Matthew Lindsay, Francesca Masserdotti, Edoardo Reverberi, Giovanni Rinaldi, Dawid Roszkowski, Nikki Sedigh, Wilusty Tengara, Zhouyi Tu & Meng Wang.

12–28 January 2023, Work shown, in excellent company, at the Forum Stadtpark, Graz. The exhibition was conceived and curated by Diskursiv (Julian Brües, Michael Hafner, Katharina Hohenwarter, Philipp Sternath).

Happy to participate in the first Architekturwoche Basel 2022, Reale Räume, as part of the 'Open Office' format.

Wednesday, 11 May, 12:00–17:00, Open to the Public; Address: Atelier #10, Am Kesselhaus 13, Weil am Rhein, DE

...

*Independently, on Saturday, 14 May, from 17:00 onwards (after Open House Basel) we will also plan an apéro at the atelier, to which all are welcome.

Invited to design an installation for a group exhibition about Japanese influence on European architects. Participating offices: Arrhov Frick, Atelier Amont, Eagles of Architecture, Fala Atelier, Frundgallina, Kawahara Krause, NKBAK, Studio Maks, Studio Spazio, UNULAUNU. 'Dialoge Japan : Europa' curated by AIT and Nils Rostek (Kollektiv A). The exhibition takes place at the ArchitekturSalon Munich, and from there moves on to Hamburg and other locations.

Invited to present the process of a built work at Garagem Sul CCB, Lisbon, PT

'Building Stories' is an exhibition about what cannot be easily perceived at first glance in architecture: an exhibition about how architecture is produced and built. Building Stories is the representation of an abstract landscape made up of architectural fragments. Like a permanent construction site, it emphasises the dimensions of the exhibition space as if it was a piece of land or a contemporary industrial ruin where it is easy to imagine the cold smell of fresh cement and the sound of heavy machinery. The intent is to transcend the limits of the museum space and focus on architecture as a discipline.

A publication on Kasuien, 1958–60, the annex to the Miyako Hotel in Kyoto, designed by Togo Murano, is in preparation ...

Diskursiv No.2, Colors

December 2024

12 × 18,5 cm, 384pp., 150 color and b/w

ISBN 978-3-98612-136-5

E-Book ISBN 978-3-98612-137-2

Color has always been a powerful tool in architecture: it can influence perceptions of space and form, convey meaning and intention and guide the viewer’s sensory experience. However, it has lost importance in contemporary architectural practice and teaching.

Compiled by the Graz-based research collective Diskursiv, this volume explores the discipline’s shifting attitudes toward color and its use by architects today. Approaching the topic on a theoretical level, the contributors stress color’s potential impact and make an impassioned case for its return to building discourse. Against the dogma of the universal white box, they advocate for color’s rediscovery as a central instrument of architectural practice.

Das Haus im Buch: Bücher von Menschen, die Architektur lieben, Park Books, Zürich, 2024

ISBN 978-3-03860-355-9

Une maison imaginaire en Sardaigne, L. Amont, 2017; Text and project published in Classeur 02, Mare Nostrum, 2017

(La version française suit ci-dessous)

Generally, while traveling, I imagine what my own daily rhythm would be like if I might be living wherever I find myself at that moment. How I could, to degrees: adapt or resist, integrate or withdraw into myself. Would I stubbornly continue my old habits… or not? If not – why? It is something I have done since childhood, but motivate myself to go on further with, now, as someone who would like to build, and as someone without many ties to my place of birth. It helps me engage with the place at hand, understanding its specific values, through a critical lens, in an optimistic sense

[..]Invited to contribute a text to the publication, Reminiscence, edited by Benedict Esche & Benedikt Hartl.

Preview a video of the contents

314 Seiten, 100 Abbildungen, 20,2 x 25,2 cm

Verlag: ea Edition Architektur, München, 2016

ISBN 9783941145115

“… You were off sailing in the sea of red. Do you know how it hurts your eyes to stare at the horizon? If you stare at the horizon long enough, all you can see is fire. The entire line of the horizon is burning. Fires as far as the eyes can see ...”

–

Fire is of course very real with concrete effects, but also abstract. It seems to us to be the same, no matter where it occurs, unlike this dry rock in my hand, here, or that rock, wet from the rainstorm, lying, half-embedded within the earth among the plains of North Dakota. This quality of fire lends itself (and the potential it has for material change) towards a smooth mental linking from one specific space and place to another.

Logan Amont, 14.11.2023

–

A short annotation, for Women Writing Architecture, on a recent publication about the life and work of Judith Chafee, an architect who worked from and mostly within Arizona.

–

‘Fuck you Mr. Smith’, wrote a teenage Judith Chafee (1932–1998) to her principle upon graduating (she had discovered the board of her high school had revealed her religious origins to the universities she had applied to, which at that time had a limited quota for Jewish students – she was anyway eventually offered admittance to all the colleges she had hoped to potentially attend, but her anger apparently lingered) …

… We need something to symbolise our lives. In a world in which everything has turned into interchangeable parts, a person wants to cry out, 'Yes, here I am!', and so proclaim that we live in the space between life and death. (Yosizaka Takamasa, 1967)